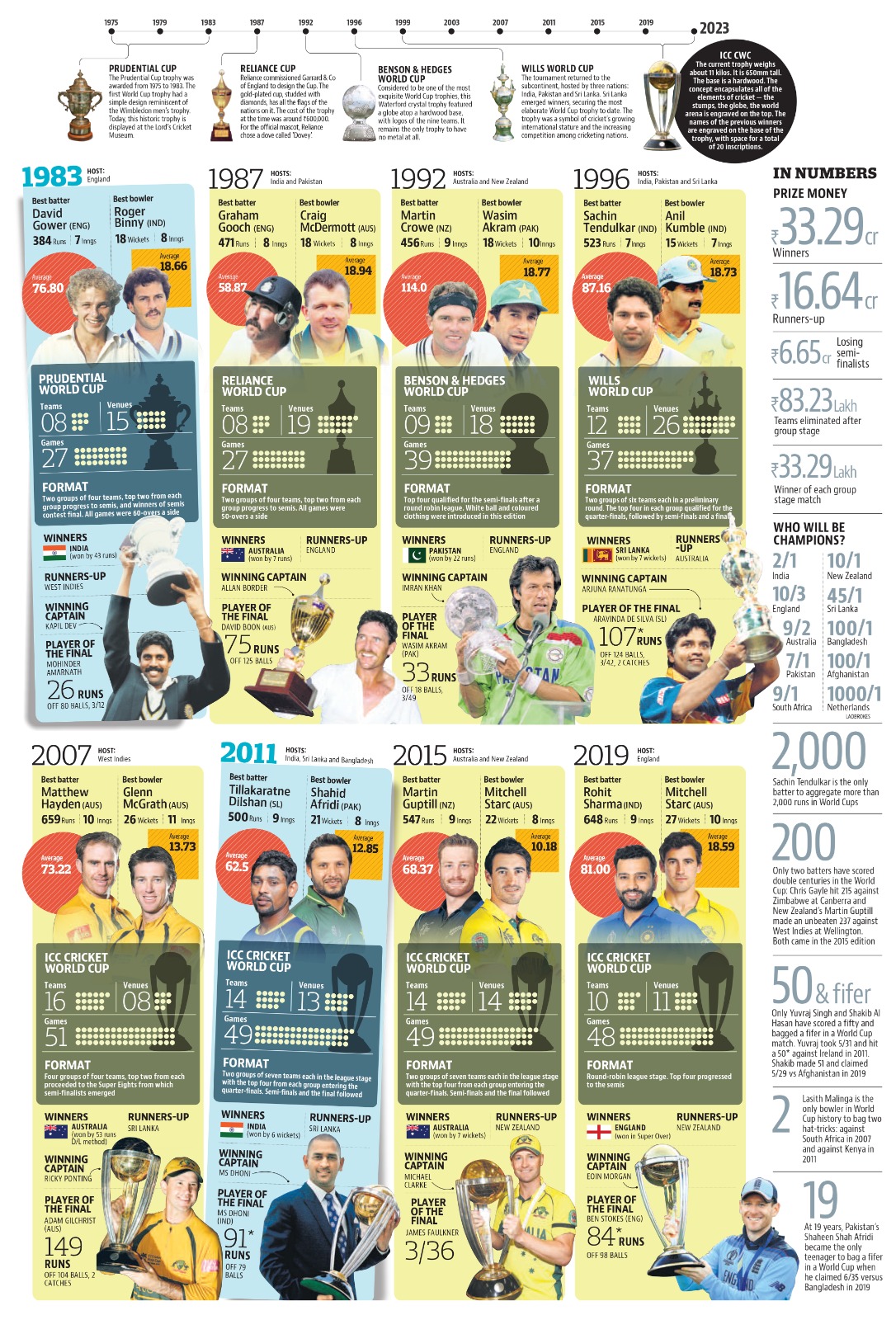

For a game that has existed for almost two centuries, cricket never had a proper grading system till the 1975 Prudential World Cup. It was an experiment to begin with, a careful dipping of the toes into a format that had to be devised in 1971 when an Ashes Test was nearly washed out at the Melbourne Cricket Ground. The basics hadn’t changed. Sixty overs a side with the Dukes ball, white flannels, white sight screens in day games that had to get over before sunset — one-dayers were literally one-day adaptations of Test matches. Till coloured clothing, white Kookaburra and floodlights, made a splashy entrance in the 1992 World Cup.

Since then, every World Cup was like a timestamp on the evolution of the game. Nearly 50 years into the existence of the original cricket World Cup, and there are bound to be vast tracts of fond remembrance despite the dipping primacy of international cricket. Imran Khan coming out of retirement to lead Pakistan to their only World Cup win was just the boost subcontinent cricket needed after India’s maiden triumph in 1983. Sri Lanka joined that league four years later, sparking a rush among other nations to learn and compete. Enter Bangladesh, followed by Afghanistan and who knows, very soon Nepal too.

The game started to change as a result. Spinners started opening the bowling, middle overs became more productive, more sixes were hit, wrist spinners came to the fore and preserving wickets for a slog-overs dash became a thing. Records tumbled too. When Viv Richards hit 181 against Sri Lanka during the 1987 World Cup, nobody thought it could be broken in two decades. That record stood for eight years. Not till the 2019 World Cup did we have a tied final that ultimately had to be decided on boundary count. By pushing the game to its limit, every edition of the World Cup gave us new ways to appreciate, understand and love cricket even more. The shortest format, T20, may have done some incalculable good, but without the ODI World Cup, cricket wouldn’t have achieved the qualifying markers of a sport courting global recognition.

Two eras, two superpowersWhat separates a once-in-a-lifetime team from the greatest sides? Traditionalists will naturally side with Test accomplishments — the longest unbeaten streaks, most wins in a row, and the kind of statistics that drip invincibility at home and away. How about adding a few World Cup wins as well? The argument is simple: If a complete cricketer is expected to switch seamlessly between formats, why can’t entire teams do the same? Australia and West Indies stand out on this front, dominating the ODI scene for nearly 40 years.

Eleven Test wins in a row between March and November 1984 underlined the ruthlessness of West Indies but a greater measure of their success were the 15 years between 1980 and 1994 when they hadn’t lost a Test series. Now factor in the World Cup wins in 1975 and 1979 along with the 1983, final and we have a largely unchanged side that dominated in both formats for nearly 20 years.

It’s not as if there was a huge gap between West Indies and other teams. Sure the cricketing world was still getting accustomed to the rules and expectations of a new format during the 1975 Prudential Cup but the Packer Series had done its bit to elevate Australia to that level as well. England, too, in all fairness, were always the team to beat given they were playing hosts the first three editions. And by the mid and late 1980s, India, Pakistan and New Zealand also grew into credible opponents. Which is why Australia’s unfettered success speaks volumes about their understanding of the game.

Australia’s dominance can be essentially broken down into two phases—the watershed win in 1987 under Allan Border followed by a period of rebuilding that saw Mark Waugh, Shane Warne, Glenn McGrath and Ricky Ponting come up the ranks in a team toughened to its core by Steve Waugh. West Indies had Viv Richards, the then most successful opening pair in Desmond Haynes and Gordon Greenidge, a venerable captain in Clive Lloyd and a fearsome pace quartet but Australia were so gifted even Michael Hussey had to wait till almost 30 for his ODI debut. The man who he replaced was Michael Bevan, arguably the best ODI finisher ever who retired in 2004 with an average of 53.58 — easily the highest in that decade.

In 2003, Australia were at the zenith of their ability, pummeling India in a one-sided final. But a real curveball was the 2007 World Cup, an indefinitely long and highly mismanaged tournament that witnessed the quick implosion of India and Pakistan, the death of Bob Woolmer, and a chaotic final. Australia however, navigated through that mess to remind the world an incredible third time in a row how they were the best team by a distance. In continuity though, it actually capped a stupendous run spanning six World Cups out of which Australia had won four finals, lost in one (1996) and almost made the semi-finals in their maiden home appearance, in 1992. That box too was ticked in 2015 when Australia mowed New Zealand to win their fifth World Cup.

The rise and rise of India

India woke up to one-day cricket on 25 June, 1983 when an unfancied side, led by a young Haryanvi named Kapil Dev Nikhanj, defeated the mighty West Indies in the World Cup final. Later that year, a silent coup was staged when NKP Salve, IS Bindra and Jagmohan Dalmiya got the World Cup out of England and into the subcontinent, triggering a tectonic shift in cricket geopolitics. Not only was the Western bloc comprising England, Australia and West Indies breached but also for the first time was the World Cup going out of England riding the precondition of rotation, giving it a truly global touch.

It didn’t take long for problems to pop up on other fronts. Barely a year before the World Cup, a military flare-up at the border prompted England and Australia to quickly flag security concerns. It took an impromptu visit by Pakistani dictator General Zia-ul-Haq during an India-Pakistan Test in Jaipur in February 1987 quickly eased those tensions. Then, when Doordarshan asked for money to broadcast the World Cup, a revenue-sharing model was devised that has worked as the basis of many broadcasting deals ever since. What really glued it all together though was Eden Gardens cramming in almost a lakh spectators to watch Border’s Australia win the World Cup. After more than a decade of English monopoly, one-day cricket had found a more interactive audience and a new order of power.

In a few years, the headquarters of the game would shift from Lord’s to Eden Gardens once Dalmiya was elected the ICC’s first Asian president. Money started rolling in, chiefly through Indian sponsors, starting with Reliance in 1987. India was smitten by one-day cricket by now, meaning they cared more about results. The 1985 Benson & Hedges Cup win was immediate affirmation that the World Cup win was no fluke. And even though India lost in the 1987 semi-finals, more favourable results had started coming in standalone tournaments like the Asia Cup or the Hero Cup. More importantly, India were slowly becoming adept at organising tournaments at home. So when the time came to bid for the 1996 World Cup, the BCCI didn’t waste any time to join hands again with Pakistan and Sri Lanka, and also hope for a win at home. That didn’t happen but the game was now spreading beyond the cities and into the heartland of India.

Nobody made the game look better than Sachin Tendulkar but it took a man from outside the usual auspices of cricket to give India what it always craved — a World Cup. The route wasn’t easy. Before the highs of 2011 came the agonising lows of 2007, when MS Dhoni’s under-construction house in Ranchi was attacked in the aftermath of India’s most embarrassing World Cup exit till date. Rahul Dravid resigned, followed by another personnel overhaul as Dhoni read out the riot act to seniors he deemed unfit, and hence unnecessary. Adding to the folklore was an eventful World Cup where India were forced to a tie by England before losing to South Africa in the group stages. Once in the knockouts though, India powered past Australia, Pakistan and Sri Lanka to finally set up a proper World Cup legacy and gain one of the finest leaders in the process.

Blueprint of a new formatIt was Martin Crowe’s brainchild but Mark Greatbatch was the one marked out to fill us in with a new approach to batting in 1992 — pinch-hitting. It was a raw, instinctive move that didn’t care much for defence or technique. All that mayhem made reasonable sense though, in that a team’s run rate could get a major fillip. Innings could be restored or given a head start, matches could be salvaged or won. Though bold, the strategy seemed one-off, till it reinvented itself in 1996, and again in 1999, ultimately leading to the birth of a new format altogether.

Without Greatbatch, there could have been no Sanath Jayasuriya and Romesh Kaluwitharana, no Adam Gilchrist, no Virender Sehwag, no Chris Gayle and definitely no T20s. Back in 1975, when the game hadn’t exactly warmed up to its one-day avatar, Sunil Gavaskar had infamously scored 36 off 174 balls after England had piled on 335 in 60 overs. The target seemed insurmountable then, and Gavaskar naturally wasn’t bothered to change gears. Now, it can be chased in 40 overs only because Greatbatch was the first to dare to think outside the box. What makes him truly a visionary is the fact that all this transpired in 1992, when coloured clothing and white balls had just made its entry but the game was still deeply entrenched in the basics and skills preached by Test cricket.

One rule change, however, caught the batter’s eye. This was the first time the fielding circle rules were being tweaked, allowing only two men outside the ring in the first 15 overs, and four after. Crowe deployed spinner Dipak Patel to open the bowling and the stocky Mark Greatbatch to open the batting. In another World Cup cycle, Sri Lanka came up with possibly the most explosive opening pair ever and made attacking the bowling in the first 15 overs a thing. Other teams quickly followed suit, bringing in different alterations and modifications. Gilchrist emerged as a specialist wicketkeeper-batter—another trend that quickly caught on — thwacking the new ball out of shape rendering the middle overs almost redundant after a point in time.

Then came Sehwag and Gayle, all of whom were major proponents of taking advantage of the new ball and fielding restrictions. With the audiences’ span getting regularly distilled into 10 or 15 overs of murderous batting, a new format was only but an expected adaptation.

Yet, as we go into another World Cup, we await the emergence of another trend that will set things up for the next World Cup cycle; set teams up for future glory. There will always be a few surprises but how many of them will stick and change the game? That’s the thing worth keeping an eye on.

Subscribe today by clicking the link and stay updated with the latest news!” Click here!

Subscribe today by clicking the link and stay updated with the latest news!” Click here!Catch all the Latest World Cup news and Live score along with World Cup Schedule related updates on Hindustan Times Website and APPs

#World #Cup #trendsetter #defines #international #cricket